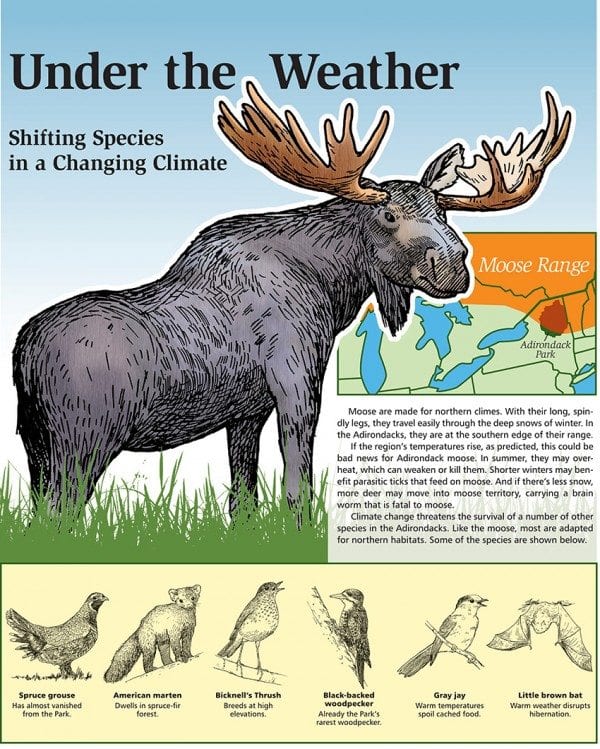

Climate change poses a threat to moose and other life forms—plants and animals—at the southern edge of their range in the Adirondacks.

By Mike Lynch

On a warm day in June, state wildlife biologist Ben Tabor knelt in a dark forest in the northern Adirondacks, peering through his binoculars at a dark shape a few hundred feet away that he suspected was a moose with a GPS collar. After a few minutes, he moved forward for a closer look.

Photo by Mike Lynch

“There’s our moose,” Tabor joked after discovering the shape to be a rotting tree on the forest floor.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

It wasn’t the first time this happened. Moose steer clear of people and are hard to spot in the forest. The moose he was looking for is one of a dozen with GPS collars that the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and several partners are keeping track of as part of a multi-year study of the Adirondack moose population.

The study began only last winter, but the results so far are surprising. Adirondack moose appear to be healthy and growing in numbers, in contrast to trends at similar latitudes in other states. Moose populations in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and especially Minnesota have declined sharply in recent years.

Scientists have said warming temperatures caused by climate change are a big reason for the moose decline in other states and pose a threat to Adirondack moose as well.

Winter ticks are taking much of the blame for the decline in the Northeast. Moose have been found with thousands of these ticks, which bleed the animal and can cause anemia and death.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

How does that relate to climate change?

Winter-tick populations are believed to be higher when winters are shorter and springs are warmer. Engorged female ticks drop off moose in the spring, and if they fall onto bare ground, they stand a better chance of surviving to lay eggs. Their survival rates drop significantly if the snowpack lingers long into spring.

“They’re all pointing their fingers at climate change,” Tabor said about the moose declines. However, he cautioned that climate change’s effects are complex and often interwoven with other phenomena, such as habitat fragmentation, pollution, invasive species, and pests and pathogens.

“

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

It’s not just one thing. When you say climate change, it’s not like you can just walk out and find it and pick it up and [say], there’s the problem,” he said.

Adirondack moose may be doing better than their counterparts because of their low density, Tabor said. For one thing, the moose have ample habitat and food. For another, there is less chance that they will transmit winter ticks and disease.

Perhaps the sharpest decline in moose has occurred in northwest Minnesota, where the population plummeted from an estimated four thousand in the mid-1980s to a hundred or so today. Researchers attribute the decline largely to liver fluke (a parasite), malnutrition, and climate change.

Moose evolved to live in cold climes. Scientists say that persistent warm weather makes them vulnerable to overheating. High temperatures cause them to expend more energy and increase their respiration rates. With average temperatures forecast to rise, Adirondack moose face an uncertain future.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

“The one big concern that we have in the Adirondacks is temperature,” Tabor said. “We’re at the fringe of the moose’s range. Basically, there’s no moose south of here because it’s too hot.”

In New York State, moose do not live south of the Adirondacks, though the occasional specimen will wander into the suburbs of Albany. Small populations also are found in forested areas in Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Climate-change models also predict that the Adirondacks will see less snow in the future. This poses another problem for moose. With their gangly legs, moose are well suited to surviving in deep snow, whereas white-tailed deer avoid deep snow. If there is a lack of snow, the two species’ ranges overlap—and deer carry a parasitic brain worm that is deadly for moose. As part of the moose study, researchers will monitor snow depths in the northern part of the Adirondack Park.

The big picture

Scientists say climate change has been occurring for at least a century. Between 1895 and 2011, average annual temperatures in the Northeast increased by nearly two degrees Fahrenheit, while the average annual precipitation increased by about five inches, according to the 2014 National Climate Assessment.

Photo by Larry Master

Temperatures are expected to rise faster this century. If carbon-dioxide emissions continue to rise, a warming of four and a half to ten degrees is projected by the 2080s. If emission rates are reduced substantially, the temperature is still projected to increase three to six degrees.

If those predictions bear out, many species besides moose are likely to be impacted. Scientists say boreal plants and animals— those adapted to northern climes—are especially vulnerable because, like moose, they are at or near the southern limit of their ranges.

Scientists believe that if, as predicted, spruce-fir forests significantly decrease in the Adirondacks, birds that dwell in this habitat also will decline. One species, spruce grouse, is already rare in the region. Another, Bicknell’s thrush, is relatively rare globally. Two others, boreal chickadee and the bog-nesting rusty blackbird, already appear to be declining in the Park and other parts of the United States.

“We’re probably seeing the end of them being a primary component of the Adirondacks bird fauna,” said Michale Glennon, an ecologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society in Saranac Lake.

Photo by Larry Master

Glennon added that she has seen greater declines in some of the resident (or year-round) species than in some of the migratory species (which arrive in spring to breed). “That’s interesting to me because it’s the opposite of what is predicted by some of the vulnerability literature,” she said.

Researchers say migrants may have trouble if climate change disrupts the timing of seasonal phenomena. For instance, birds may arrive in their breeding habitat too late to fi nd berries or insects that they rely on for food.

The gray jay is one resident species in decline in the Adirondacks. In winter, the birds cache food such as insects and berries under tree bark. Studies in Ontario’s Algonquin Park found that warming temperatures spoil the food. This is especially troublesome because gray jays reproduce in late winter when there isn’t much food available in the environment.

The Bicknell’s thrush, a migratory species, is in danger because it breeds only in high-elevation spruce-fir forests—habitat that could vanish if the climate warms. “The thought is that it will be pushed off the mountaintops as those mountaintops become more vegetated or the vegetation characteristics change,” Glennon said.

As boreal birds disappear from the Park, southern birds are expected to move in. The Carolina wren, tufted titmouse, and mockingbird are three species that appear to be showing up in the Adirondacks in greater numbers. Although scientists cannot pin the northward expansion solely on climate change, it’s believed to be a factor.

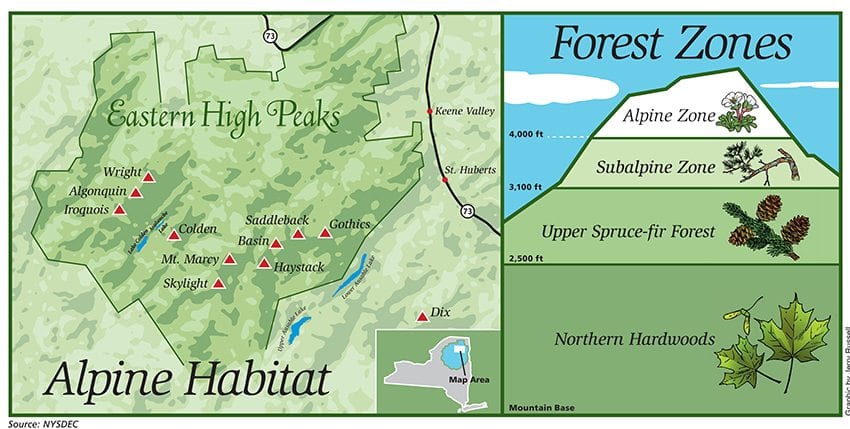

Boreal habitats such as alpine meadows, high-elevation forests, and certain types of wetlands are expected to be greatly impacted over the next hundred years. In contrast, deciduous forests may not see significant changes in tree species for several centuries or longer.

Montane spruce-fir forests are thought to be especially vulnerable. There are about 213,000 acres of this habitat in New York, according to a 2013 report by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) for DEC. Most of this habitat is in the Adirondacks. Although it represents less than 1 percent of the state’s land mass, it’s 20 percent of the montane spruce-fir habitat in the Northeast.

In the Adirondacks, this forest is generally found above three thousand feet, where temperatures are a few degrees cooler than in the lowlands. The forests are dominated by red spruce and balsam fir, with a sparse understory. The ground cover is dominated by moss and lichens. Besides Bicknell’s thrush, other birds that dwell in spruce-fir forests include blackpoll, Cape May, and bay-breasted warblers.

According to the NWF report, a rise of five or six degrees in average temperature could spell the end of this habitat in the Adirondacks. Other boreal habitats at risk are bogs, fens, and peat lands, which cover more than eighty thousand acres in New York State, again mostly in the Adirondacks. These are generally found in cold climates where soils are saturated and acidic and the growing season is short and wet.

In the Northeast, the growing season is expected to increase anywhere from twenty-nine to forty-three days by the end of the century, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture report. It’s predicted that spring will start ten to fourteen days earlier and that the changing and dying of leaves in the fall will be pushed back.

“These changes will have a profound impact on the region’s forests and water cycle including productivity, plant nutrient uptake, streamflows, and wildlife dynamics,” according to the USDA report.

Weather records for New England show that the average annual precipitation has increased 3.7 inches, or 9 percent, in the last century, according to the USDA. The agency’s report, a review of scientific literature, says the trend is expected to continue and bring more extreme storms. Despite the additional precipitation, climate models also predict longer dry periods. There will be less groundwater and stream water in summer, and as a result, forests will be less productive and more vulnerable to pests and disease.

One pest of concern is the woolly adelgid, an aphid-like insect from Japan that sucks the sap of eastern hemlocks, destroying the trees. It is now found in the Catskill Mountains and lower Hudson Valley. For the moment, its northern spread is held in check by the severity and duration of winter. If the climate warms, however, the adelgid is expected to move farther north, perhaps into the Adirondacks.

Photo by Larry Master

A reduction in groundwater and stream water might affect the food web. One species at risk from climate change is the little brown bat, which already has been decimated by white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has swept through bat populations in recent years. The little brown is a small bat with high energy demands that feeds almost exclusively on insects that reproduce in water.

“Climate change may influence the availability of those insects by altering precipitation, stream flow, and soil moisture,” the USDA report says. A lack of food could be especially detrimental to bats as they rely on stores of fat to make it through winter hibernation. Lack of nourishment could also suppress reproduction.

Moreover, an increase in winter thaws—another prediction of climate models—could cause bats to awaken before spring and deplete their fat stores. Wood frogs and other amphibians run the same risk.

Hope for forests

Despite dire predictions for boreal habitat, Charlie Canham, a forest ecologist with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, sees good things in the near future for northeastern temperate forests—the type of forest that covers most of the Park.

“From the perspective of a warming climate, the eastern temperate forests of North America are probably the most resistant to climate change of any ecosystem on the planet,” Canham said. “You just think of these species. Sugar maples grow from Nova Scotia to northern Georgia. It’s nowhere near its northern limit of its cold distribution in the Adirondacks, and so a three-degree warmer temperature makes it sort of like Maryland, where it’s perfectly happy.”

Some reports assert that sugar maples will not do well in a warming climate, but Canham said they will do extremely well in the next 150 years. He also said the Northeast has a lot of young forests that will grow and mature in the years ahead. Over the next few centuries, he added, the biomass of northeastern forests will likely double.

“Yes, there’s going to be changes in species, but the big changes in species mix are due to natural succession, given the land-use history of the past and the current harvests,” he said. “Some species are going to decline simply because the logging regime and fire regime that gave rise to those species a hundred years ago is no longer present in the landscape and other species are favored.”

Canham said that his scientific models show that four hundred years from now northern forests with beech, hemlock, sugar maple, and red spruce likely will have more white pine and tulip trees. Beech and maple will still be present, but he expects them to be in fewer numbers. The forests are expected to have more oak and hickory trees.

“You’ll have a forest that looks a looks a lot more like Kentucky,” Canham said.

Birds moving up mountain

By Mike Lynch

A survey of birds on Whiteface Mountain has found that many species have moved uphill in the past forty years, possibly in response to climate change.

New York State Museum curator Jeremy Kirchman and Alison Van Keuren, a volunteer, conducted bird surveys on the 4,867-foot peak in 2013 and 2014. Their work replicated surveys by two University at Albany biologists, K.P. Able and B.R. Noon, in 1973 and 1974.

The surveys included looking and listening for birds at seven spots on Whiteface. Able and Noon also surveyed Nippletop (like Whiteface, one of the Adirondack High Peaks) and two Vermont mountains, but that work wasn’t duplicated.

“There’s a lot of bird species that are now found all the way to the very top of Whiteface Mountain that were not found at the very top forty years ago,” Kirchman said.

He said fourteen birds were found in the highest elevations on Whiteface in this most recent survey as compared with just seven located forty years ago. The American robin and yellow-bellied flycatcher are among the new birds now found at the highest elevations on Whiteface. The yellow-bellied flycatcher has moved roughly a thousand feet up the mountain while the robin has gone up about 1,400 feet.

“Usually those changes are due to some kind of perturbation like habitat change,” Kirchman said. “But in this case, it’s probably driven by warmer temperatures because the habitat has not changed at all.”

Kirchman did not look into why the changes occurred for any of the birds. He said it is possible robins and yellow-bellied flycatchers could have moved up the mountain for other reasons. For example, their populations and overall ranges may be growing.

Kirchman said he hopes to survey Nippletop next summer and plans to do surveys every five years on Whiteface to document bird-population changes. He noted that several scientific models and papers (including one authored by him) have predicted that many, or all, of the boreal birds will disappear from the Adirondacks before the end of the century because of rising temperatures. Many live in bogs and other lowland boreal habitats; others live in spruce-fir forests located just below tree line on mountains. Many come to the Adirondacks to breed in the warmer months.

“Boreal chickadee, gray jay, yellow-bellied flycatcher, blackpoll warbler, Bicknell’s thrush are all boreal-forest specialists that meet the southern periphery of their breeding ranges right here in the Adirondacks,” he said. “If global warming is pushing birds north and uphill, then we should expect to see these changes in the Adirondacks first. It could be a sort of canary in the coal mine for boreal-forest birds responding to climate change at a continent scale because we’re in this interesting place.”

Park’s forests keep carbon out of the air

By Mike Lynch

The Adirondack Park helps to fight global warming by carbon sequestration: its forests pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and store it.

Trees and green plants absorb carbon dioxide— the principal greenhouse gas—and convert it into sugar, cellulose, and other carbohydrates used for nourishment and growth.

Scientists believe younger, rapidly growing forests are most effective in pulling carbon dioxide out of the air. Older forests also absorb carbon dioxide, and their wood is largely made up of carbon. By storing the carbon, trees keep it out of the atmosphere.

Colin Beier, a forestry professor at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, said the Park’s mix of Forest Preserve, where trees grow undisturbed, and working forests, where trees are harvested and new ones take their place, is a good combination for carbon sequestration.

Beier noted that wood products such as lumber and furniture store carbon long term. On the other hand, if wood burns or rots, carbon is released back into the atmosphere.

Charlie Canham, a forest ecologist with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, said forests throughout the Northeast have enormous carbon-sequestration potential in the coming decades.

“We actually predict biomass across the landscape to almost double over the next hundred years,” he said. “That’s basically because there’s a lot of young forest on the landscape. If anything, climate warming, with the slight increase in precipitation, could increase that.”

Leave a Reply