Mill, hatchery, snow gunners and public water supplies top the list of permitted water users

By Zachary Matson

Whiteface Mountain’s website the Monday before Thanksgiving promised skiers a Black Friday deal: Snow. At least on the slopes. Conditions may apply.

“Our snowmakers will be hard at work,” the state-operated ski resort teased in its conditions update.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

Ever since Lake Placid in 1980 hosted the first Winter Olympics to use man-made snow, the ski center’s workers have supplemented Mother Nature with a firehose of supplemental snow. It’s produced in a complex maze of pumps, pipes and powerful snow guns, fueled by the West Branch of the Ausable River.

The snowmaking operation, intensive in labor, energy and water, levels out inconsistent snowfall to help meet visitor expectations, entice international competitions and maintain a centerpiece of the region’s culture —as scientists lament the gradual “demise of winter” in the Adirondacks. An agreement with the state Department of Environmental Conservation allows the Olympic Regional Development Authority to pump 6,000 gallons of water per minute from the river, with restrictions at lower flows. In recent years the ski center used about as much water during the winter months as Lake Placid’s public water supply uses throughout the year.

“We wouldn’t be in business if we didn’t have it,” said Aaron Kellett, ORDA’s general manager of Whiteface Mountain.

Whiteface is just one of the entities in the Adirondack Park operating thanks to abundant water. The park’s vast water resources support the business of snowmaking, public water supplies and, especially, paper production.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

Nearly 100 permitted water users with the capacity to withdraw at least 100,000 gallons per day combined to pump over 12 billion gallons in 2022 from lakes, streams, rivers and natural underground stores.

One user, the Sylvamo Paper Mill in Ticonderoga, long known as International Paper, used about half of that total tonnage, according to an analysis of monthly water withdrawal reports submitted to DEC from 2009 to 2023. The mill employs around 600 people.

The state-operated Adirondack Fish Hatchery cycled over 1 billion gallons of water through the fish-rearing facility each of the past eight years—the second biggest user in the park.

Public water supplies, the next largest category of water use in the region, combined to account for nearly 4 billion gallons pumped in 2022, about one third of the water reported used that year (and still 32% less than the paper mill). The region’s public water providers supply drinking water to around 65,000 residents and thousands of annual visitors to the park.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

A thirsty paper mill

The Sylvamo mill draws its water from Lake Champlain’s southern narrows—each year relying on about 0.08% of the lake’s estimated 6.8 trillion gallons of water—and on average releases over 15 million gallons of treated wastewater back to the lake each day.

State inspectors consistently noted satisfactory conditions during visits in recent years, according to records, but officials issued the mill violation notices in June 2024 and June 2020, after workers spilled methanol last summer and released wastewater sludge in 2020.

Sylvamo, based in Memphis, Tennessee, declined an interview and facility tour. The company, established as a spinoff of International Paper in 2021, also operates mills in South Carolina, Brazil, France and Sweden.

The company aims to reduce its overall water use 25% by 2030 and create water stewardship plans for all its mills, according to its 2023 annual sustainability report.

The Adirondack Explorer thanks its advertising partners. Become one of them.

But in 2023 Sylvamo increased its water use 7% over its 2019 baseline, according to the company report.

The mill combines water with wood fiber ground and cooked into pulp to make paper. When first combined into so-called “furnish,” the product is 99.5% water. A fast-moving conveyor belt and screen start to draw the water before it is further pressed by heavy rotating cylinders. Finally, a series of dryers evaporates the remaining liquid before the paper is finished, cut to size and packaged for shipping. Without water there is no paper. The mill relies on a complex of artificial wetlands to filter and clean its wastewater before discharging it back to Lake Champlain.

The resource of water

Water has always been central to the Adirondack Park, which was partly established to preserve consistent flows into the state canal system, and its abundance is seen as a compelling draw in the face of diminishing water sources elsewhere.

But will climate change, which scientists predict will mean a mix of increased precipitation and extended dry spells, strain precious water resources in the future? Downstate counties this fall were put under a drought warning, with officials recommending voluntary water conservation and advising public water supplies update drought contingency plans.

Research at Paul Smith’s College led by Curt Stager in 2022 found that climate has and will continue to alter the region’s fragile ecosystem and cultural identity. If the planet continues carbon emissions at current levels, Stager’s team estimated, the Adirondacks could see winters shortened by as much as a month by 2100 as springs arrive earlier and summers lengthen.

Even the best-case scenario projected a gradual decline of winter conditions for the foreseeable future.

On the slopes, shorter winters and fewer cold temperatures will increase pressure on snowmakers. At Whiteface, pumphouse 1 draws water from the Ausable a short distance from the main visitor lodge; the mountain reduced its use in recent years after installing volume controls on the pumps.

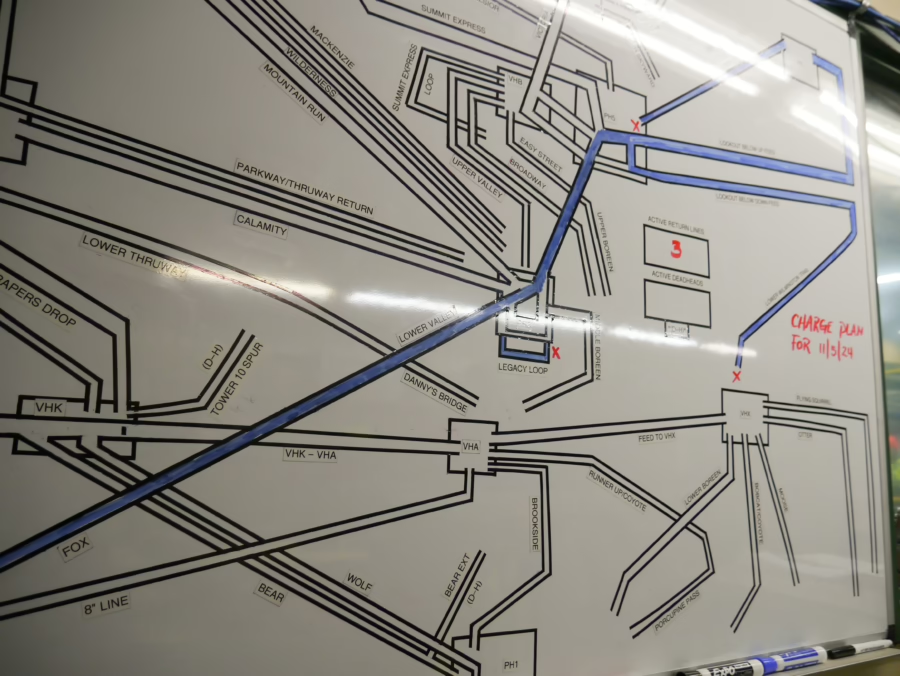

Pumphouse 2, though, is the real power center. A control desk there monitors and operates a network of 50 miles of pipes across the mountain. Eight 800-horsepower air compressors supply snow’s second most important ingredient.

ORDA is moving toward greater efficiency with investments in equipment and replacing pipes first installed ahead of the 1980 Olympics. A reservoir would further help the center maximize its snowmaking by providing storage to optimize river flows, Kellett said.

This winter Whiteface is testing use of a snowmaking additive called Snomax, a protein composed of dead organic material that weighs down artificial snow so more of it lands on the slopes. But none of the improvements enable them to make more snow for less water.

“The goal is to make more snow faster, for less money and to reduce our carbon footprint,” Kellett said.

Other permitted water users—a list that excludes the many residents and businesses in the park that rely on well water—include mining operations, state prisons and Adirondack Farms in Peru, the park’s single agricultural operation with a withdrawal permit.

Eleven golf courses in 2022 reported using a combined 100 million gallons of water to keep the greens green.

Jim Connors, the longtime course manager at Saranac Inn Golf and Country Club, the course with the highest water use reported, said unlike most Adirondack courses Saranac Inn also waters its fairways.

“We only water when we need to,” Connors said. “We only water when there isn’t enough rain.”

The Adirondack Fish Hatchery near Lake Clear, the only state-run hatchery within the blue line, raises all of the Atlantic salmon stocked by the state, as well as endangered round whitefish. Drawing water from Little Clear Pond, which flows through pipes lying beneath the new Adirondack Rail Trail, and a small collection of wells, the hatchery uses about 3 million gallons of water per day.

The steady flow of cold, oxygenated water cycling through incubation trays, raceways and large artificial ponds is essential to raise tens of thousands of fish as they grow to six or seven inches before being stocked across the Adirondacks and the state—over 30,000 pounds of fish a year. To keep the fish healthy, the hatchery’s gravity-fed water system pushes each new gallon of water through the hatchery in a matter of hours. Water in storage ponds cycles out within about 90 minutes.

“The fish need fresh water,” said Matt Jackson, the hatchery manager. “If it’s stagnant, they won’t be happy.”

Like the Whiteface snow that eventually melts and runs back to the Ausable, the water used at the hatchery makes its way back into the watershed. After passing through the hatchery raceways and tanks, it drains to concrete settling ponds, where sediment and nutrients filter out and are removed by hatchery staff.

The hatchery adopted more stringent protocols to address concerns about phosphorus discharging to Upper Saranac Lake, improving its fish food and increasing water sampling. Under its wastewater discharge permit, the hatchery can release 4.1 million gallons of used water a day into Hatchery Brook, which flows to Upper Saranac Lake.

“Everything that comes in goes out,” said Jim Daley, DEC’s superintendent of fish culture.

Stay connected

This article appeared in a recent issue of Adirondack Explorer magazine.

Start your subscription today!

Leave a Reply